New Thinking on Mass Hypnosis (Formation / Psychosis) from senior scholars, Paul Frijters, Gigi Foster and Michael Baker at Brownstone Institute. They believe that we need to think and act bigger against totalitarianism. We are not that small or downtrodden, nor as isolated. Most importantly, they know that we can win, and we will.

I’m sharing this as a guest article because it provides yet another viewpoint to my own thoughts on mass hypnosis.

This article was originally published at Brownstone Institute under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

New Thinking on Mass Formation (Psychosis)

As individuals slowly emerge from the fog that descended on them in March 2020, the sense of disorientation and anxiety is palpable. Some of those who took part in the fanaticism and bullying are rewriting or memory-holing what they actually said and did. Others have proposed a pandemic amnesty, as if everyone is just waking up after a drunken night and vaguely remembered they did some stuff they probably shouldn’t have, but hey, it was all well-intended. Everyone makes mistakes so let’s just move on.

What actually happened to the millions of people who kept the covid circus going? What forces were operating on their minds that are now finally starting to recede? Will another madness descend, and if so, why and when?

In his book, The Psychology of Totalitarianism, professor of clinical psychology Matthias Desmet talks about ‘mass formation,’ a phenomenon historically given the moniker ‘crowd formation.’ Desmet claims that most of the world population coalesced into a crowd in the early part of 2020. The narrative of that crowd came to dominate the public sphere, the political sphere, and the private sphere, making it classically ‘totalitarian,’ an event Desmet puts in a broad historical and technological perspective. The issues he raises are fundamental for understanding what is likely to happen next, and for charting our own roles as members of Team Sanity in the next few years.

Crowds formed in early 2020

Desmet’s central thesis is one with which we wholeheartedly agree, and it is nearly identical to what appears in our own writings: the populations of many countries became crowds in February-March 2020, obsessed with seeking protection from a new virus. The elites responded to the call for sacrifice and safety by issuing propaganda and ordering health rituals that were eagerly embraced and amplified by their populations. People abandoned their individuality and critical thinking, using their minds not to question the totalitarian controls that removed their basic freedoms, but to rationalise and evangelise them.

In describing how individuals think and behave in these crowds, Desmet draws on centuries of sociological thought, including the works of Elias Canetti, Gustav Le Bon, Hannah Arendt, and particularly the Frankfurt School. He admitted in his July 2022 interview with John Waters (and again in a nearly identical interview with Tucker Carlson in September 2022) that it took him a few months in 2020 to recognise that crowds had formed. We too only recognised the crowd formation several months into the madness, in about June 2020. It had been so long in the West since this phenomenon occurred on this scale that the very possibility seems to have slipped out of our collective consciousness. We know of no commentator who identified the crowd formation right at the start and wrote about it.

Although the covid crowds are now slowly dispersing, the damage is so great and the lessons that humanity’s actions during this period have taught us are so unpalatable and challenging that they send a shudder through those of us who didn’t participate.

The population led the government, not the other way around

One key implication of the crowd dynamic is that there is no single culprit, no head of the snake, no enemy that planned the covid saga ages ago. In crowds, both the population and its leaders get caught in the maelstrom of the adopted narrative, dragging them all into a wild ride that, unlike a ride in an amusement park, has no predictable pathway or ending. Yes, the elites take on the roles of jailers and autocrats, but these are roles demanded of them by their own populations. Should they refuse to play as requested, they would quickly be cast aside and replaced by others who are prepared to do the business. As Desmet points out, removing any part of the elites would have made no difference, as it would make no difference now.

A telling example of this dynamic played out in London in March 2020. Rishi Sunak, the then UK Treasurer (now Prime Minister), recently reminded us of what happened in those days: the medical establishment and the politicians did in fact try to follow the received wisdom of 100 years of medical science and resisted locking down, but such was the uproar in the British population that the government caved in and instigated lockdowns anyway.

One of us was in London then and can verify from personal experience that this is exactly how it was. The UK government’s feeble resistance crumbled under a tidal wave of fear. After the politicians had succumbed to public pressure, the institutional medics fell in line, pushing to the forefront media hounds like Neil Ferguson, who had a special penchant for playing up apocalyptic scenarios that lent themselves to totalitarian solutions.

By implication, Desmet dismisses the idea that the Chinese were behind it all, or that the World Economic Forum, the CIA, the WHO, or some small group of cliquey pro-lockdown medics plotted the catastrophe like the evil geniuses you see in James Bond movies. Sure, several groups sniffed a chance at more power once the stampede was underway, or advanced their long-held agendas and wish lists, but no one saw it all coming or had worked out how to manipulate billions of people to fall for it.

The trajectory of stocks in those early days exemplified the surprises: huge drops (including, for example, in the Big Tech sector) in February-March 2020, followed by huge increases for particular sectors (like, for example, Big Tech) after May 2020 when the markets started to work out what had really happened and who was benefitting from the new realities. If anyone had known in advance how all the chips would fall, that person would now be the richest individual in the world.

We completely agree with Desmet’s thinking on all of this, although the implication of no ‘grand conspiracy’ is irritating for many in Team Sanity who like the simplicity of a culprit on which everything can be blamed. It’s the easy way out. Yet, is it really likely that the many US judges across the country who were reluctant to enforce the US Constitution were somehow all directed by nefarious Chinese?

Is it useful to think that the decisions by individual EU countries to mask and inject young children to within an inch of their lives is really all part of a WEF plot hatched 20 years ago? No. One should blame those US judges and EU legislators themselves for what they decided to do, both because the ‘grand conspiracy’ alternative is extraordinarily unlikely and because assigning individual blame for individual actions is a pillar of Western judicial thinking. Holding people accountable for what they did is much more confronting and politically difficult than externalising blame, but it is what needs to be done in order for justice to be restored.

Did too much ‘enlightenment’ prime populations for crowd formation?

Desmet argues — and here we part ways with him — that populations had become psychologically primed for crowds in recent decades. He also proposes solutions that we find unconvincing.

Desmet identifies rationalism, mechanistic thinking and atomisation in modern society as jointly having caused a high ambient level of loneliness and anxiety. He then claims that the rise in these phenomena created a large group of people eager to adopt a common cause, so as to fill the void in their lives. This is in fact an old argument, also run by Theodor Adorno of the Frankfurt School, writing in the 1950s. Charlie Chaplin’s brilliant movie Modern Times had a similar flavour: a factory worker on an assembly line, feeling alienated from others, lonely, and impressionable, becomes a sitting duck for the call of the crowd.

It is easy to agree with Desmet if you look only at the US or China. One can easily argue that in these two countries in the lead-up to covid, alienation was rising and mechanistic, and ‘rational’ thinking had created a belief that complex social problems could be controlled and remedied with technology. Further pre-2020 trends in consumerism and the gradual replacement of many social relations by direct interactions with the state in health, education, and other domains can well be said to have catalysed the emergence of an atomised and lonely population, desperate for common threats to bind them.

The rise of what we have elsewhere called ‘bullshit jobs’ that leave people without a sense of worth or dignity, digital replacements for in-person relationships and communities that cannot offer the security and affirmation available from the in-person varieties, and high levels of inequality that make many people feel inferior, were arguably like fuel on the fire. These elements are all consistent with Desmet’s contention that modernity itself had readied humanity for a new era of crowds.

However, let us take a wider point of view, in which this reasoning begins to look less valid as an explanation for what happened in early 2020.

For one, the covid panic swept around the whole world, across many different cultures and many different types of economies. For Desmet’s story to be true, the same ‘dry tinder of modernity’ argument should hold everywhere, and it should also be true that the few countries in which the madness was staved off (Sweden, Nicaragua, Tanzania, Belarus) should be united in lacking that dry tinder.

Yet the panic did not turn only the peoples of the lonely West into crowds, but also those living in the emotionally warmer regions of Latin America, the largely agricultural societies of sub-Saharan Africa, the strongly religious and family-oriented Arab gulf countries, and the super-secular state of Singapore.

Why did some countries escape the madness, if not because they had escaped the corrosive elements of modernity? The main reasons appear to have more to do with random luck than with these countries’ relationships with technology or with the rationalist beliefs of the Enlightenment. Tanzania’s president immediately countered the narrative, trying to protect his country. Nicaragua was wary of any medical story coming from beyond its borders.

Belarus was being run by a dictatorship that did not want to weaken its own country at that time. Sweden had plenty of mechanistic rational thinkers, but also happened to have a quite peculiar set of health institutions manned by particular people, Anders Tegnell and Johan Giesecke, who pushed back on behalf of the people they served. If we had to put these separate stories under one heading, it might be “courageous patriotism serendipitously surfacing in the right place at the right time.”

As empiricists, we cannot help observing that the international pattern of crowd formation seen in 2020 does not fit the argument that modernity created the ‘dry tinder’ allegedly required for the covid crowds to form. It does not fit the claim of our fellow Brownstone author Thorsteinn Siglaugsson, who was following Desmet’s argument, that “a healthy society does not succumb to mass formation.” We think this is too optimistic, and moreover too convenient.

The empirical record also does not fit Giorgio Agamben’s explanation for what happened. He notes that decades of power grabs perpetrated under safety theatre created a population used to being ruled by fear and rulers used to wielding fear. That story rings true for Italy (on which Agamben was commenting) but does not explain the emergence of covid crowds everywhere in the world in 2020.

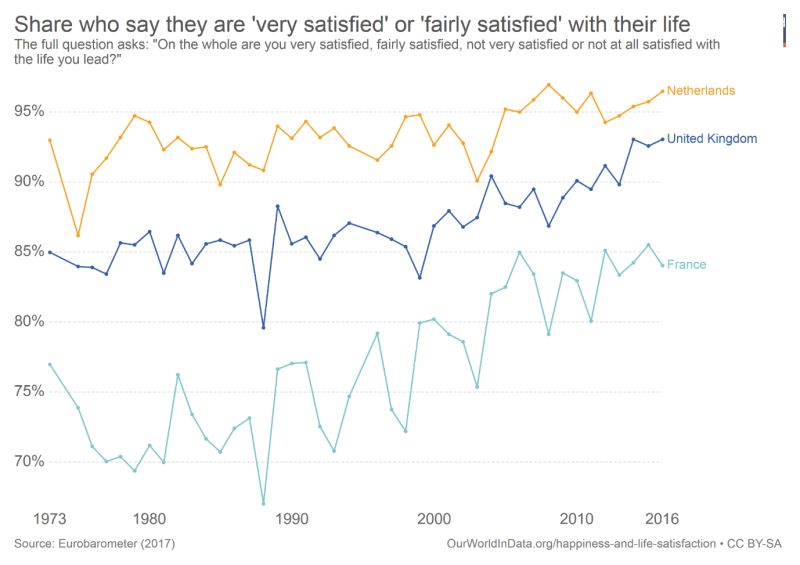

Another fact discordant with the Desmet hypothesis is that well-being and social connections were in fact improving for decades in Europe in the lead-up to 2020, as reflected in the data graphed above. The early 2000s was a golden age of positive psychology, with thousands of self-help books on mindfulness and wellness selling millions of copies, and whole countries adopting community-formation policies like the well-being initiatives of the UK National Lottery. The US might have become lonelier in the past 30 years, but that is not true for much of Europe, which seemed to have worked out how to have peaceful and prosperous societies. Societies sporting many corrupt governments and high inequality, yes, but happy and sociable populations anyway.

A good example of an extremely socially connected and happy place full of confident citizens believing in themselves was Denmark, a country consistently in the top five happiest countries in the world for a decade. Yet, Denmark was a very early lockdowner (following Italy). The Danes did snap out of it relatively quickly, but they were swept along initially just like everyone else, notwithstanding their high social cohesion, low levels of corruption, and lack of loneliness.

We deduce that there was nothing special about the mindset of humanity in January 2020 that made it more susceptible to crowd formation. A more convincing narrative, to our minds, is that the potential is always there in every group and every society to turn into a crowd, merely to be awakened by a strong emotional wave. In the case of covid, it was a wave of fear awakened by a blizzard of hyped-up doomsday reports on mass media about a novel respiratory virus.

The key thing explaining how the covid fear swept across the world is then (social) media. New information systems allowed for a self-enforcing wave of anxiety to be transmitted person-to-person at scale across the mediums of information sharing, in an extended and deadly worldwide super-spreader event.

Yes, that wave was manipulated and amplified for all sorts of reasons, but the existence of shared social media across the world was the real enabler of the emergence of the covid crowds. Mass media is the tinder for global crowd formation, not a mechanistic view of the world, the rationalism of the Enlightenment, or the supposed loneliness of people with meaningless jobs. In our view, humanity does not need to be anxious in order to be moulded into a crowd. All that is needed is a megaphone of one sort or another, a medium through which excitement gets shared with many. With mass media spanning the globe, a major worldwide panic was bound to happen sooner or later.

Should we turn our back on ‘enlightenment?’

Desmet explicitly opposes the ideals of the Enlightenment, following the same line of thought as the Frankfurt School. The argument goes that the process of reasoning about others creates an ‘othering,’ by virtue of making others an object of analysis and thus something that is placed slightly out of reach of more immediate empathy. Desmet notes that this ‘othering’ disconnects people from their own empathy.

He is right about the effects of ‘othering,’ but that effect is not unique to reason. Any form of commenting on others, such as trying to explain the behaviour of others in terms of, say, their relation to a god, has that same effect of turning other people into objects of thought. The religiously excused ‘othering’ of heretics in the Middle Ages allowed crowds to burn their fellow men at the stake.

A similar argument goes for mechanistic world views. Humans have used tools to influence nature for millennia, changing their environment purposefully and constantly. While the Enlightenment saw the breakthrough of a specific type of thinking about others and a whole new set of tools, it didn’t invent othering and environment-moulding, but rather it led to the replacement of previous ways of doing these things that were no less ‘othering’ or divorced from nature.

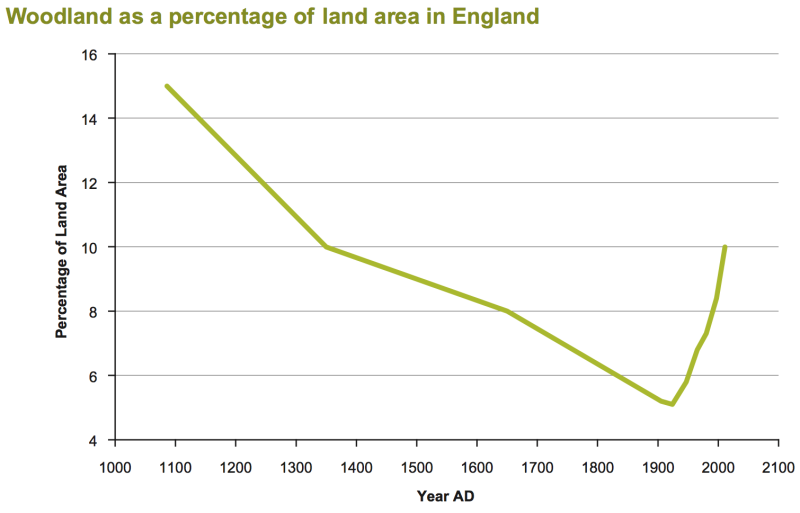

As a simple example, one might reflect on the fact that England was virtually covered with forest before humans colonised it, after which there was a steady decline in forest cover for centuries as land became used for agriculture, with forest cover increasing again only in the last 100 years (see below). It’s hard to argue for picking out the Enlightenment period (post-1700) as particularly ‘divorced from nature.’

Mechanistic and rationalist thinking have also brought humanity huge benefits that we cannot imagine our species giving up. Mechanised agriculture, mechanised mass transport, mass education, mass information, mass production: these are quintessential parts of the modern economy that have helped humanity grow from 300 million poor people in Roman times to nearly 8 billion much wealthier and longer-lived people today.

There is simply no going back on that progress. Humanity does not give up the axe it invented to chop wood simply because the axe will also be used to kill others. Rather, humanity develops shields, as a countermeasure to the heightened killing potential, while further perfecting the axe as a wood-chopping tool. That is surely what we are going to do this time too. We are not going to regress on technology, including technologies of the mind that are right now working so well for us in so many areas.

More deeply, while we sympathise and agree with Desmet’s soulful appeal for acknowledgements of the limits to rationality, the human need for mysticism and empathic connection, and the good that comes from courageous, principled decision-making, we do not think that such appeals help societies make much progress. For one, moral appeals from the sidelines always sound a bit desperate. The truly powerful have armies and media to enforce their will and crush any such calls into oblivion. Also, when society really wants to remember lessons far into the future, it looks for something to write into history books that is less fickle than morals.

Edmund Burke, the English conservative philosopher, captured this fact nicely with his contention that it is through our education, laws, and other institutions that we remember the deep knowledge learned over centuries as to what works and what does not. Learning from our current mistakes will similarly have its long-term effect via change to our institutions. We won’t stop mass education, mass transport, national taxation, or most of the other activities societies have adopted over millennia in order to thrive in competition with other societies. We will simply tweak the institutions involved in the current set of problems using the insights gleaned from the mistakes and successes of the last round of history.

In the long run, then, the name of the game is not moral appeals but institutional evolution. Even the French revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks, who both used brutal methods to overhaul their societies, in reality kept the vast majority of the existing institutions in place. The French revolutionaries did not destroy the existing bureaucracy or army structures they inherited from the royal court of the Bourbons, but expanded and modernised them.

The Soviets did not do away with large agricultural estates they inherited from the Russian aristocracy, but collectivised them. The French did not do away with the existing scientific institutions of the late 18th century that had been royally commissioned, but set them to other tasks.

The Soviets did not demolish the harbours and other infrastructure the Czars had left them, but built more of them. In similar fashion should we expect our time to have its imprint on the institutions handed down to future generations. To our minds, thinking about how to change and adapt our institutions is the main intellectual program of Team Sanity: to have good plans ready on how to improve things in many areas, both locally and nationally.

While Desmet dreams openly about the ‘end’ of mechanistic, rationalist, and Enlightenment thinking, we do not see those elements disappearing any century soon. Yes, humanity might stumble upon better community narratives, and manage to embed a greater general appreciation of the limits to reason and control – an area in which we have many suggestions to offer – but that is not really an end to modernity.

Are crowds really mad?

Even more deeply, we somewhat disagree with Desmet that crowds are innately ‘out of their minds’. Desmet himself avoids the word ‘psychosis’, but does speak of crowd members being as if under hypnosis. Having witnessed the devastation wrought by the covid crowds around the world, it is appealing to ‘other’ the crowd phenomenon itself and put it, and those who succumb to it, into a box labeled ‘poor mental health.’ Yet crowds are more like high-octane groups: running on an unusually high level of intensity and connectedness, they are extremely focused and allow no diversity of openly expressed opinions or pursued interests.

Crowds may lead to destruction, but they are merely more intense, faster to act, and more aggressive towards non-believers than ‘regular’ groups. They are mad from the point of view of those not going along with them, but do they emerge or survive due to a dysfunctionality – a psychosis? If so, then most of the world is psychotic, drawing into question whether that word then really means anything.

Crowds can in fact be agents of creative destruction, often leaving their countries with new institutions that turn out to serve a useful function and are kept for centuries. Just think of our systems of mass education that push a common view of history, combined with a single language, a single set of ideals encoded in law, national festivities, allegiance to the flag, and so on.

Sociologists and writers like Elias Canetti have long recognised that all this is crowd-propagated propaganda. It is called the ‘socialisation’ function of education, and it is part of the heritage of the nationalistic crowds of the 18th to 20th centuries, kept on because it is so efficient in galvanising peoples into nation states.

Desmet’s view of crowds is medicalised, but in the long arc of history, crowds and the wars they initiate can be seen as mechanisms of creative social destruction. Crowds are certainly extremely dangerous, but one should not only fear them. Just as our ancestors did, we face deep social problems, like inequality, for which stampeding crowds may be the only realistic solution.

Whither the stampede?

We agree completely with Desmet’s judgment that the stampede is not over yet, even though in several places the covid madness is coming to a clear end. Like him, we believe that populations are now susceptible to even more draconian and violent forms of totalitarianism, partly because the elites are busy installing an increasing number of totalitarian control structures, partly because populations are now eager to avoid the truth of what they have been party to, and partly because perhaps as much as 95% of the people have become poorer and angrier as a result of being exploited while in their ’crowd state.’

Desmet’s key observation is that in many Western countries and regions, the political, administrative and corporate elites have now become used to totalitarian control. Those elites use propaganda to overwhelm independent thinking in the population, thus keeping the crowd alive, while moving from excuse to excuse until they are unseated. That eventual unseating will require a major collapse of their totalitarian structures, so quite possibly that will only occur after the crowd turns even more destructive.

In a recent interview, Desmet opined that we are easily looking at another eight years of crowd madness in much of the West. We think in similar time frames, and for the same basic reason: the structures of totalitarianism have grown stronger, particularly with the normalised acceptance of government propaganda adopted by private media companies and the relentless sharing of that propaganda across social media platforms, which are also busy censoring alternative views. The elites have now realised the true extent of the power they wield and they are hungry for more. They won’t stop until they are ousted. People with that kind of power rarely, if ever, do.

Like Desmet, we also believe that totalitarianism will come crashing down eventually, because totalitarianism is very inefficient and loses out against other models of society. Dark times nonetheless lie ahead, for years at least.

What to do?

This brings us to the final and most speculative aspect of Desmet’s thinking: his call for ‘Truth Speak.’ He wants Team Sanity to sincerely speak truth to the crowds, believing that crowds start exterminating ideological rivals from within as soon as the unwelcome truth no longer buzzes around, and that this process will lead to the eventual fracturing of the crowd.

We could not agree more with the way Desmet describes the role of the Truth Speaker. We have each played this role during these times and have felt personally the poetic and empathic tendencies that it draws upon and enhances. This has been and continues to be a deeply spiritual journey.

Yet, playing that role is enough to nourish ourselves intellectually, or to inspire others. We need to act on the assumption – the belief – that we will eventually win.

This means that Team Sanity should turn its mental energies to designing different or amended institutions for the whole of society to adopt when the madness has come crashing down. We should compete for space with the totalitarians where we can. Local groups that educate their own children are important, even though they are an open and hence a somewhat risky challenge to totalitarianism. Ditto for health organisations, Team Sanity consumer initiatives, new free academies, and other structures in which we can all live more freely.

While the inner world of the Truth Speaker might be our last refuge, even if we feel we have nothing else and are completely overpowered by fanatical totalitarians who deny us all other space and companionship, we need to think and act much bigger. We are not that small or downtrodden, nor as isolated. We can win, and we will.

Authors

Paul Frijters

Paul Frijters, Senior Scholar at Brownstone Institute, is a Professor of Wellbeing Economics in the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics, UK. He specializes in applied micro-econometrics, including labor, happiness, and health economics Co-author of The Great Covid Panic.

Gigi Foster

Gigi Foster, Senior Scholar at Brownstone Institute, is a Professor of Economics at the University of New South Wales, Australia. Her research covers diverse fields including education, social influence, corruption, lab experiments, time use, behavioral economics, and Australian policy. She is co-author of The Great Covid Panic.

Michael Baker

Michael Baker has a BA (Economics) from the University of Western Australia. He is an independent economic consultant and freelance journalist with a background in policy research.

Start speaking out by sharing this article

Other Articles

Embrace Your Creativity: Harnessing the Free Power of Writing

Harnessing the Power of Writing for Personal Freedom Are you ready to embrace your creativity and experience the power of writing to set yourself free? In a world that often

Videos: Media Interviews

Media Interviews: Deb Donnell, Author Radio New ZealandSounds HistoricalJim Sullivan19 June 2011 BreakfastTV One15 February 2013 Canterbury LifeCTV25 February 2013 Watch Watch Watch ABC Radio Network 360DocumentariesGretchen Miller9 June 2013

How Dare They Cancel the English Language!

Have you noticed they want to cancel the English language? Along with everything else. Well, this is something that is being politicised in the exact same fashion that George Orwell